Policy debate in Ireland

Current context

Citizens' Assembly on Drug Use

2023 - Citizens’ Assembly on Drugs Use has been established to consider the legislative, policy and operational changes Ireland could make to significantly reduce the harmful impacts of illicit drugs on individuals, families, communities and wider Irish society.

The Citizens’ Assembly on Drugs Use is made up of 100 people, including 99 members of the general public and one independent chairperson. The members of the Assembly will be asked to take into consideration the lived experience of people impacted by drugs use, as well as their families and communities, and to look at international best practice.

Information about the Citizens' Assembly and videos of the Assembly meetings is available here

- 2023 October: The final meeting of the Citizens’ Assembly on Drugs Use, issues 36 recommendations: https://citizensassembly.ie/citizens-assembly-on-drugs-use-publishes-full-36-recommendations/

- 2024 January: Report of the Citizens' Assembly on Drug Use published. Report Here

- 2024 May: Membership of Oireachtas Joint Committee on Drugs is finalised. The committee was established to examine and act on the report from the Citizens' Assembly on Drugs Use.

- 2024October: Oireachtas Joint Committee on Drugs issues Interim Report

See the Citizens' Assembly section of the Citywide website here

Health Diversion Programme

In August 2019 the Government decided to implement a Health Diversion Programme, for those found in possession of drugs for personal use. Previously, those found in possesion of drugs could be prosecuted under the criminal justice system and acquire criminal convictions, making it difficult for these people to find work, travel abroad and access services such as housing and education. Additionally, the stigma associated with criminal conviction made it difficult to access addiction support services.

Under this new approach, when a person is found in possession of drugs for personal use the Government has agreed to implement a health diversion approach whereby:

- On the first occasion, An Garda Síochána will refer them, on a mandatory basis, to the Health Service Executive for a health screening and brief intervention;

- On the second occasion, An Garda Síochána would have discretion to issue an Adult Caution.

Under the programme, a person found in possession of drugs for personal use is diverted to the HSE for a health screening and brief intervention, known as SAOR (Support, Ask and Assess, Offer Assistance and Referral).

The steps in the Health Diversion Programme:

Step 1: Gardaí identify a person in possession of drugs for personal use.

Step 2: Gardaí refer the person to attend a SAOR screening and brief intervention provided by the HSE. This could be done online so appointments can be confirmed on the spot and happen in a timely fashion (a few days).

Step 3: The person attends the SAOR intervention with a dedicated healthcare worker.

Step 4: If a person is identified as having or at risk of problematic use, they are offered appropriate treatment or support. Their attendance at treatment/support is voluntary.

Step 5: Other referrals may be identified and facilitated, such as social services or harm reduction programmes.

Step 6: The person’s attendance at the brief intervention is confirmed to the Gardaí (with the person’s consent).

On the second occasion that a person is found in possession of drugs for personal use, An Garda Síochána would have the discretion to issue an Adult Caution. Details of the programme here

Working Group on alternative approaches to the possession of drugs for personal use

Action in the National Drugs Strategy:

Action 3.1.35 of the new NDS ‘Reducing Harm, Supporting Recovery – a health-led response to drug and alcohol use in Ireland 2017-2025’, which was launched in July 2017, calls for consideration of approaches taken in other jurisdictions to possession of small amounts of drugs for personal use, in light of the Justice Oireachtas Committee Report. In November 2017 the Department of Health and the Department of Justice and Equality, who have joint responsibility for the action, announced the setting up of a Working Group to carry out this task.

The Report of the working group was published in March 2019 and is available here: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/30887/

Private Members' Bill May 2017

A Private Members' Bill tabled by Independent Senator Lynn Ruane entitled the Controlled Drugs and Harm Reduction Bill 2017 was adjourned on May 31st in Seanad Eireann. The passage of the bill to Committee Stage was postponed, pending the publication of the National Drugs Strategy.

In May 2016, following a general election in February, a new government was formed in Ireland. In its Programme for partnership government, the new government pledged: ‘We will support a health-led rather than criminal justice approach to drug use including legislating for injection rooms’ (p. 56). It should be noted that in the election which preceded the formation of the government, almost all political parties committed to a health –led approach to drugs in their manifestos. The process of developing the new National Drugs Strategy (2017-) needs to reflect on the policy and practice implications of this shift in the government approach to drug use.

While the Irish government has begun to engage in the debate on decriminalisation in recent years, the origins of the debate in Ireland date back over 20 years when civil society first began to have discussions on the option and it is civil society organisations that have led and shaped the debate in the intervening years.

Origins of the Debate

1990s...

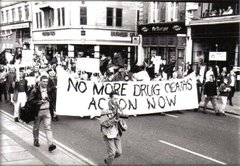

Initial attempts to start the decriminalisation debate at community level took place in the mid 1990s, but were quickly overtaken by the scale of the drugs crisis affecting many local communities, in particular in the most disadvantaged areas of Dublin. A public meeting was organised in the North Star Hotel in north inner-city Dublin, by the Inner City Organisation Network (ICON), to talk about decriminalisation. But women and mothers at the meeting asked why they were talking about decriminalisation when there were no services available and their children were dying. The focus of the meeting shifted from decriminalisation to the ‘emergency situation’ and the urgent need for services.

A street campaign began which campaigned to draw political attention to the drugs crisis – the slogan of the campaign was “Addicts we Care, Pushers Beware”. This reflected the view that alongside the immediate need for services, a strong criminal justice approach was also needed to address drug dealing in local communities. People who used drugs and people who sold drugs were seen as clearly distinct groups and drug dealers were characterised as major criminals making significant amounts of money from the trade. Tough laws that provided for long prison sentences for drug dealers were actively supported by community organisations.

A street campaign began which campaigned to draw political attention to the drugs crisis – the slogan of the campaign was “Addicts we Care, Pushers Beware”. This reflected the view that alongside the immediate need for services, a strong criminal justice approach was also needed to address drug dealing in local communities. People who used drugs and people who sold drugs were seen as clearly distinct groups and drug dealers were characterised as major criminals making significant amounts of money from the trade. Tough laws that provided for long prison sentences for drug dealers were actively supported by community organisations.

2000s...

In subsequent years the views of community organisations on the effectiveness of these tough laws began to alter as their experience of the drugs issue deepened. Their experience included seeing people becoming ‘victims’ of sentencing policy; for example, young people who had been pressurised into holding large quantities of drugs were facing long prison sentences. Parents were starting to see the laws intended to target ‘hardened criminals’ now being turned on their own children. At the same time, local projects involved in providing services for drug users were becoming more aware of the negative impact on people of criminalisation for drug use. This type of experience led to a change in views, as did the realisation that the legislative framework was not addressing the problem and that while methadone substitution treatment was a step forwards it was not the full or final answer.

In 2006 the Drug Policy Action Group (DPAG), comprised of interested individuals from all sectors, published Criminal justice drug policy in Ireland. The authors, Sean Cassin of Merchant’s Quay and Paul O’Mahony of Trinity College, argued that there was too much reliance on legislation and the criminal justice system for dealing with the country’s illegal drug problems and that this was creating more problems than it was solving: … it was the user who was predominantly targeted and more deeply inserted into a criminal justice system that can do little to promote personal development or the removal of obstacles to personal growth. This over reliance on the criminal system merely serves to recycle successive generations through criminal processes that become a life norm that perpetrates [sic] the criminal and disadvantaged sector (p. 4).

In 2007, around the time that the short-lived DPAG ceased to meet, CityWide became a member of the EU Civil Society Forum on Drugs, convened by the European Commission in Brussels, and went on to become a member of the International Drug Policy Consortium (IDPC),a global network promoting objective and open debate on drug policies. Through networking with people who have experience of the drugs issue in countries across Europe and the wider world, CityWide began to develop its understanding of decriminalisation as a policy option.

2010s...

In 2012 it published a new agenda for action, based on an extensive consultation with its members, which included a call for a debate on decriminalisation: ‘There is a view that much of the harm related to drug use and drug dealing occurs because of their illicit nature and that if the criminal aspect of the problem were removed then the harm would be reduced. International evidence shows that decriminalization initiatives do not result in significant increases in drug use. There is a need for an open debate about decriminalisation in Ireland'.

A conference was organised by Citywide in May 2013 “Criminalising Addiction – is there another way?” and this was the first time that all of the stakeholders in Irish drugs policy came together to discuss issues of drug policy reform and international drugs policy. At the conference there was general support for the view that a clear distinction should be made between decriminalising the use of drugs and legalising the availability of drugs, as the latter was seen as a more complex issue. Considerable follow up work was done by Citywide following the seminar with the aim of informing and broadening both political and public debate.

Two years later, following extensive debate and deliberation, in its oral submission to the Joint Committee on Justice, Defence and Equality that was inquiring into the effects of gangland crime on communities, CityWide outlined its now unequivocal support for decriminalisation:

We strongly favour decriminalisation. Currently, we make a person a criminal for using a drug. People use drugs for all kinds of reasons, including personal or social reasons. To make them a criminal for doing that makes no sense. It only adds to their difficulties and increases their engagement with the criminal justice system. We believe there should be decriminalisation, … Nobody is going as far as to suggest legalisation. However, there is a general recognition in the international drugs policy area that what we are doing now in the war on drugs is not working. Across the world, it is the poorest communities that suffer the damage. We should decriminalise drugs.

Politically, decriminalisation was first openly discussed around 2011. In that year, the junior Health Minister in charge of Ireland’s drugs strategy, Roísín Shortall, stated she had an ‘open mind’ in relation to Portugal’s decriminalisation model. By 2013, in a Dáil debate on regulating the cultivation, sale and possession of cannabis and cannabis products in Ireland, a number of TDs openly indicated their support for considering decriminalisation as a policy option. In April 2015 the call for a public debate on decriminalising the possession of drugs for personal use received the formal support of an Irish government for the first time, when Aodhán Ó Ríordáin was appointed to the position of Minister with responsibility for the National Drugs Strategy. In his first public appearance as Minister for Drugs, Ó Ríordáin announced his personal support for decriminalisation, calling for drug use to be treated as a ‘health issue’, and he set out his intention to have an open and honest debate on the issues.

In July 2015 Minister Ó Ríordáin led a think-tank discussion with all stakeholders in the NDS, including government departments, statutory agencies, community and voluntary sector representatives and Drugs Task Forces, which reached agreement to examine the issue in more detail. Also in 2015, following an initial inquiry into gangland crime in Ireland, the Joint Oireachtas Committee on Justice, Defence and Equality focused specifically on decriminalisation as a policy option, sending a delegation to Portugal to examine that jurisdiction’s approach in more detail. The Committee’s final report strongly recommended the introduction of ‘a harm reducing and rehabilitative approach, whereby the possession of a small amount of illegal drugs for personal use, could be dealt with by way of a civil/administrative response and rather than via the criminal justice route’. The Joint Committee included a number of caveats: any such scheme should be discretionary, approached on a case-by-case basis, supported by appropriate services including training and education, and treatment, and based on further research to ensure it was appropriate in an Irish context.

In the nine months that he held ministerial office, Ó Ríordáin developed his arguments for decriminalisation, emphasising the need for ‘compassion and sensitivity’ in responding to those experiencing drug problems and the need for a ‘cultural shift’ in attitudes and behaviours towards substance misusers. At the 20th anniversary conference of CityWide, in November 2015, Minister Ó Ríordáin called for a ‘national conversation’ about decriminalisation.